Beyond Engineering.

The Engineering Paradigm and Its Limitations

Over the past 30 years, organisations and institutions have increasingly emphasised engineering-based principles and applied an engineering mindset to the practice of management.

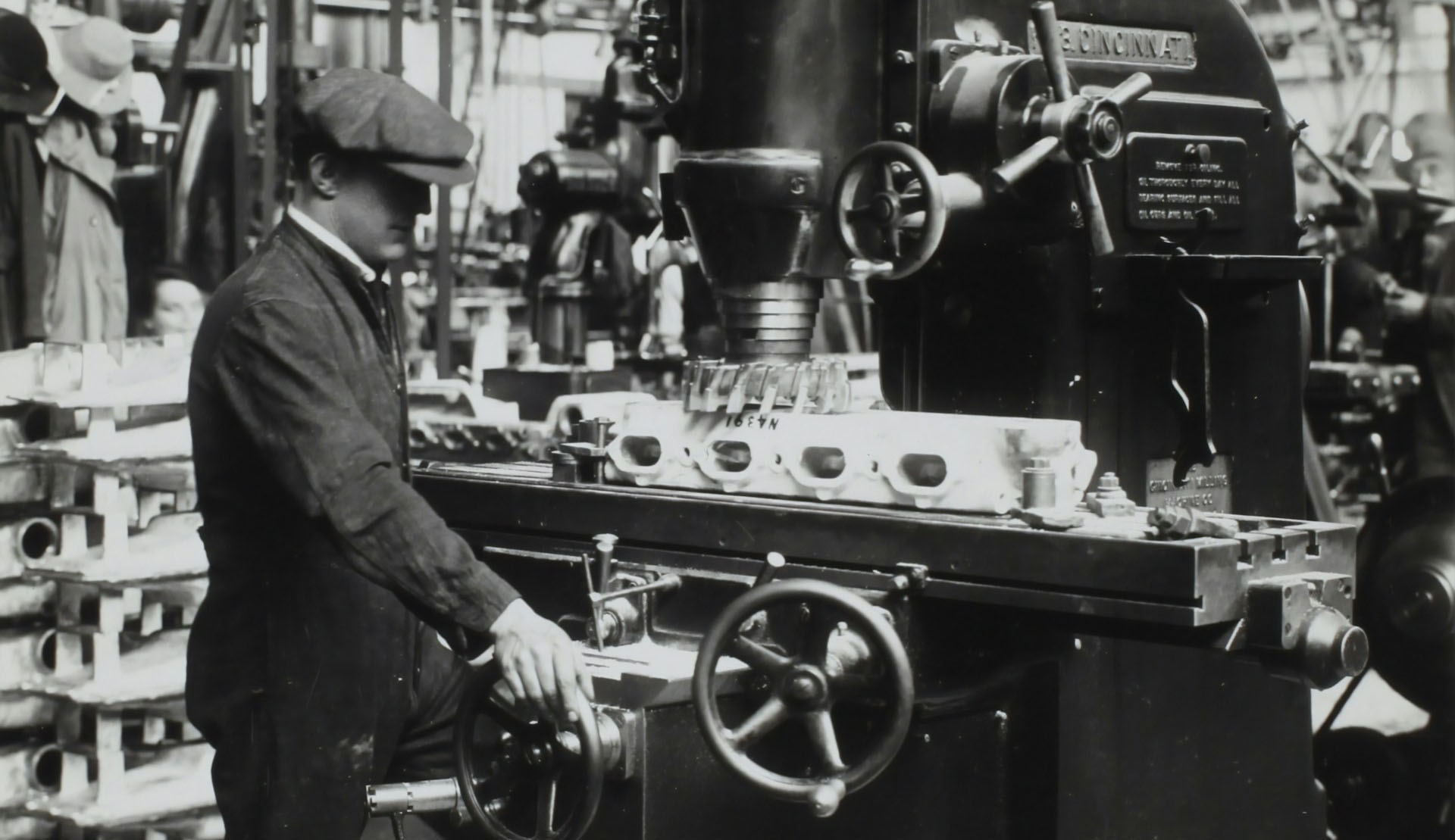

While these principles—such as stakeholder engagement (understanding stakeholders as environmental variables or component parts), discipline integration for system optimisation, quality assurance, and continuous improvement—have provided valuable frameworks for enhancing efficiency and mitigating risks, they often reduce the human element of organisations to generic component parts defined by set roles, functions and positions. In many cases, individuals are seen as cogs in the machine rather than as unique human beings with diverse skills, qualities, abilities, and knowledge that can be adapted and utilised across an organisation.

Under the engineering paradigm roles and functions are essential, the people that fill them are redundant

There are indeed particular organisational functions that need to be performed, roles that need to be filled and different people, at different times can perform these functions and fill these roles. But the engineering paradigm imagines that when the organisation is failing to function, it is the roles and functions of an organisation that require reconfiguration (restructuring). In the process its people are largely forgotten. Under the engineering paradigm roles and functions are essential, the people that fill them are redundant (in all the senses of both of those terms).

This engineering paradigm, if not tempered, can lead to a disconnect between leadership and the human assets that drive success. People are not merely job descriptions. To state that an organisation is its people is aphorism but too often in contemporary management the organisation is thought as a structure of defined roles and functions that people merely inhabit.

Toward a Living Systems Culture

There will be a collective groan from some corners of the room at the very mention of the word 'culture'. The measure of an organisation's culture is often reduced to a vague sense of how it feels to work within it at a defined point in time. The catalyst of that feeling is nearly always considered removed from the nuts and bolts (or roles and functions) 'engineering' questions regarding how the organisation works.

For that reason workers tend to hear the Executive or Human Resources (people and culture) speak of 'culture' or 'cultural change' as merely an attempt to make them feel better (mostly when they already feel bad) without ever addressing the concrete conditions that affect that feeling. Too often 'cultural change' is considered something we can effect without much (re)engineering or something that re-engineering will magically obviate any need to confront.

Reimagining Organisational Life

We need to think more deeply about what 'culture' actually means and how culture works with respect to an organisation's vitality and development. How would it change our approach to management if we thought of organisations and businesses not as something we 'built' but as something we 'cultured'? What if we treated organisations and businesses as the living organisms that they quite plainly are?

What if we treated the people that constitute that organisation not as redundant inhabitants of essential roles and functions but as essential themselves to an organisation's vitality and dynamism? What would it look like for leaders to foster a living systems culture that figures the organisation as a living organism constituted of other vital organisms (teams and people themselves) rather than as a machine made of exchangeable and reconfigurable parts?

The Organisation as Living System

A living systems culture is built on an understanding that each employee, each team of which those employees are members, the way those individuals and teams interact with each other and in relation to the wider organisation and world, is critical in sustaining a responsive, dynamic and vital organisation. In such a culture, every person is seen as an integral part of a larger whole, contributing to mutual growth and collective success. This perspective encourages organisations to view their employees, not just as workers filling specific roles, as vital and differential agents (in that their differences are valued) constituting a dynamic assemblage. It is important to note here that this can't be feigned. It is not about the employees perception or affect. It’s as much about the way the organisation employs its human resource than it is about the way the employee feels about that relationship (although this too will affect their employment). The question of individual performance becomes less one of fitting that individual to defined requirements and more of cultivating and culturing their vital contribution to the organisation as a whole.

Evolving Beyond Traditional Restructuring

In real terms this doesn't mean abandoning the idea of defined roles and responsibilities. Instead it means tempering the engineering paradigm with an understanding that those roles and responsibilities serve the development of the individual as much as they are to serve the functioning of the organisation. People will move through positions. As they do they will demonstrate different qualities, build new relationships, learn new things and achieve greater organisational perspective.

A good organisational culture is one that provides the conditions under which its organic components (its people) thrive as a function of engaging with different roles and responsibilities, and in that thriving, are empowered and motivated to understand and contribute to the vitality of the whole.

Too often organisations pull the 'restructure' lever when their organisation is not flourishing. Indeed, even within organisations that are functioning well, the engineering paradigm preaches a process of continual improvement and refinement that has seen large scale restructure become a perennial feature of corporate life.

A good organisational culture is one that provides the conditions under which its organic components (its people) thrive and in that thriving, are empowered and motivated to understand and contribute to the vitality of the whole.

There are known downsides to large scale restructures. Organisational restructures cost organisations not only money, but corporate knowledge, disruptions to relationships, challenges to adaptability, erosion of culture, resistance to change, and loss of talent. A restructure from on high, triggered and directed by an executive, is a violent cultural reset.

Very occasionally this is indeed what is required, a hard reset, but the violence is more costly than the engineering paradigm comprehends. This is particularly the case when the reasoning behind the change is poorly communicated and is executed by the engineers in the so-called 'c-suite'. Continual Improvement executed as an endless series of engineered restructures forgets the cultural discontinuity it affects at every turn. How do we work toward actually continuous improvement within and as part of an organisation if the organisational culture is continually reset? Of course a living systems culture doesn't preclude restructure, rather its approach to restructure is as a function of cultural evolution.

Cultivating a Living Systems Culture

Fostering Interdependence and Adaptability

A living systems culture highlights interdependence, adaptability, and collaboration among team members. A living systems culture fosters an environment that thrives on shared knowledge, creative collaboration, collective well-being, and mutual support. Communication and transparency become key in a living systems culture, not so much in the service of accountability (an engineering reduction of the human if ever there was one) but in the service of a vitalised, distributed, knowledge-rich and responsive network.

In such an environment, employees feel empowered to express their ideas, take risks, and contribute to the Organisation's mission and are acknowledged when they do so.

Leadership in Living Systems

Leadership plays a critical role in fostering the conditions for a living systems culture to flourish. At its core, this requires a shift from directing and controlling, to nurturing and enabling. Leaders must create spaces for open communication and experimentation where all voices are heard and ideas given space, time and resources to be tested and developed. This begins with modeling collaborative and communicative behaviors—active listening, valuing diverse opinions, and recognising team achievements. When collaboration is prioritised at all levels of the organisation, it cultivates an atmosphere where individuals feel comfortable sharing ideas beyond their designated roles.

Nurturing Individual Development

The role of leadership in a living systems culture extends beyond creating collaborative spaces to actively supporting individual growth and development. Open communication needs to be multilateral, demonstrating honesty and respect. If a person is not thriving in their work, leaders need to be equipped and empowered to have that conversation with the individual. But the conversation and its outcomes must always be two-way. The question of a failure to thrive and its eventual solution is always ecological - how can the organisation support the vital and capable contribution of the individual?

This investment in development needs to extend well beyond training - which is, of course, essential but is only the 'engineering' aspect of employee development. Organisations should provide opportunities for growth through progressive further education and experience programs, mentorship initiatives, and career advancement pathways.

The question should be more than simply how to better equip the employee for a defined function but how to support the employee in developing and realising their potential for the future. This might include developing lateral perspective and connection across the organisation as much as supporting individual career progression.

From Individual to Organisational Growth

When individuals feel valued for their contributions—not just in terms of their job functions but as multifaceted human beings—they are more likely to engage fully with their work and invest in the organisation's success. This commitment creates a positive feedback loop: as employees grow and develop their skills across various domains, they contribute more effectively to the organisation's goals and culture.

...as employees grow and develop their skills across various domains, they contribute more effectively to the organisation's goals and culture.

As much as the engineers would have our work lives reduced to the function we fulfill, we all have different relationships to work, and that relationship rarely defines us as complex multifaceted individuals. We have relationships, passions, vulnerabilities, knowledge and expertise, responsibilities and burdens that exceed the bounds of our professional work, but nonetheless affect who we are at work. Often these human elements and qualities are what drive us to want to contribute more than what is required of our role, drive us to learn and to grow, and keep us engaged.

The more an organisation can recognise that an employee is more than the role they fill at work, the more effectively that individual will thrive and feel connected in their work and their working relationships. The more an organisation is aware of the person as more than role they occupy, the more that individual can be supported holistically both at work and in the life and vitality of which work is likely only a fragment.

The Organisation as Living System

Ecological Perspective

From this understanding of individual development and growth, we can better grasp how the organisation itself functions as a living system. The sustained vitality (the resilience) of an organisation is dependent upon the networks of communication and support it establishes both internally and with the wider ecologies of which it is part.

These ecologies include the markets, communities, society and environment in which the organisation operates. While market responsiveness might seem most immediate and obvious, the organisation's relationship with these other scales, community, society and environment, is equally vital to its sustained health.

The best way for an organisation to thrive within a complex and layered ecology is to exercise an eco-logic - to understand and work in support of its ecological function(ing) and its ecological communications

We'd argue that regular auditing of the organisation's ecological function, and impact at each of these scales, can help refine and clarify its mission, ensuring that mission is indeed functioning ecologically. When we use this term, we don't mean 'environmentally', we just mean to suggest that the best way for an organisation to thrive within a complex and layered ecology is to exercise an eco-logic - to understand and work in support of its ecological function(ing) and its ecological communications.

Organising according to such a logic increases and complicates the organisations connection with the wider world - the organisation thus becomes inextricably part-of and party-to a wider ecological vitality. Another way to put this might be to say that the organisation, with an eye on its ecological functions and relations, is better placed to develop as a complex and multifaceted organism with deep and sustaining connections to the communities upon which it depends and serves.

(Photo by Museums Victoria on Unsplash)